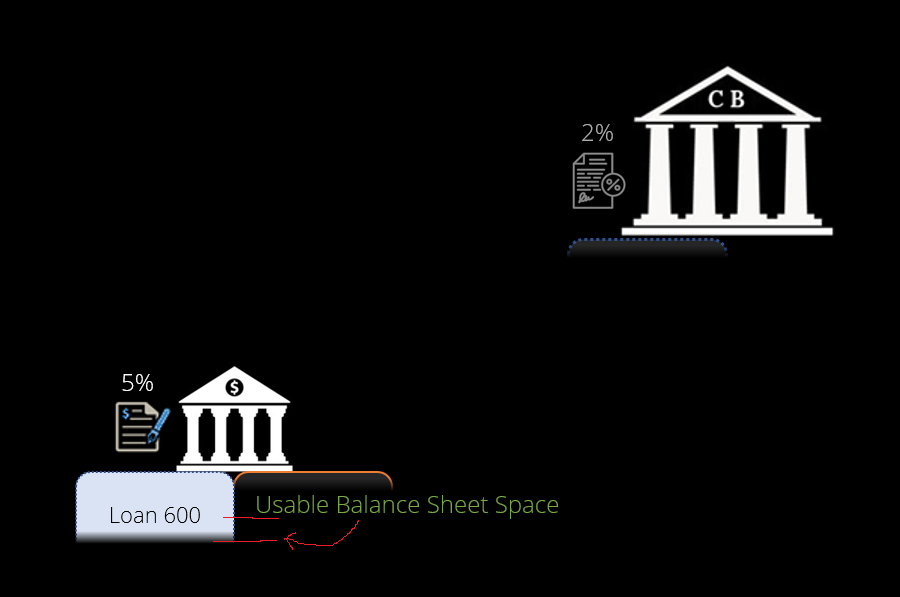

The Fed has a mandate to control prices, but asset prices aren't included in that mandate. The Fed inflates asset prices, intentionally. Again, I'm not saying the Fed is good or bad, I'm trying to get at a good description of money creation in order to trace its path through the system, we're just trying to identify where the fuel comes from in the first place. And the Fed is one component of money creation, when it marks up the accounts of its account holders, who are banks. The private banks themselves create most of the money supply.

Ok, here is a claim we can test. When a bank issues a loan, such as an investment bank, it would be interested in recouping the loan [principle + interest (risk) + inflation (expected)]. So any bank loan (money creation) would have included in it an adjustment for the inflation associated with not just this loan, but all loans, over the respective period of time. Is this adjustment for the change in total private bank lending over time (typically referred to as a 'credit impulse') reflected in bank loan documentation? Not that I am aware of.

We can also look at the change to CPI or CPI + asset prices when defaults rise, because defaulting loans means that the corresponding destroyed money is never destroyed. During periods of cascading defaults (firesales) does the CPI or asset prices rise? No, typically both decrease.

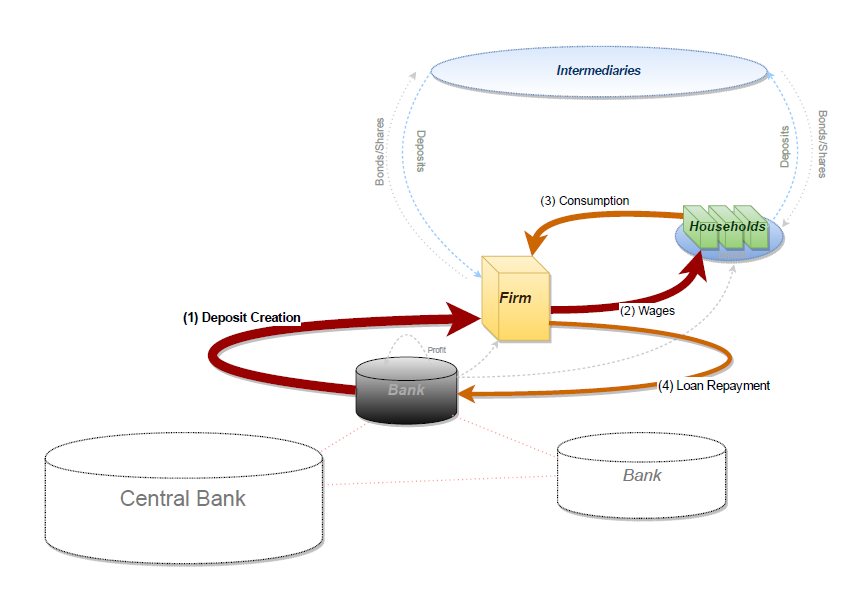

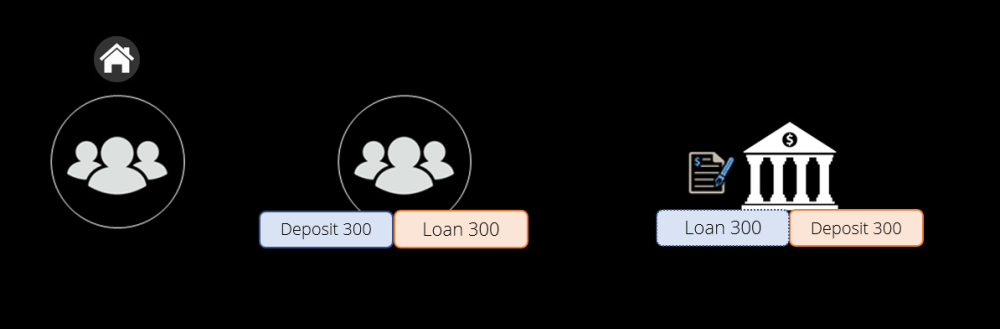

Next we can think about it from the perspective of a single loan for a business that purchases only labour, a single 'monetary circuit' (Graziani, pictured below). #1, the bank creates deposits for the firm, #2 the firm pays workers... [If all money is always inflationary, are workers wages rising? The wage contract is typically agreed to and fixed prior to payment]... #3 Workers buy and consume the output... [If all money is inflationary, are the prices for the produced goods increasing? I don't believe so, firms typically set prices equal to costs plus a markup and don't respond to immediate changes in demand. Plus, any inrease in prices means an inrease in inventory, which would mean losses for the firm and default because the workers don't have enough money to pay increasing prices for the output, they would need additional loans from the bank]... #4 The firm repays the loan destroying the money created by the bank.

Where in this circuit are prices changing because 'all money is always inflationary'?

Please see the chart I posted above, which shows the response of CPI to Fed QE operations (no correlation). I agree that the Fed causes a change in lending behaviour, and you are spot on about that increasing 'moral hazard' and potentially 'misallocating resources', and that the asset price inflation will likely reverse if the Fed attempts to unwind QE which is happening now. These are valid points--and I'm not trying to antagonize you, I like your analysis--but I want to purge from it a reliance upon commodity money first and foremost. Banks create money, gov and private banks, and they are the decision makers about where the path of our economy leads (what we make, what we consume, where its made, etc). And this is not neutral <-- not just some function of the highest rates of perceived return, but subjective decisions of imperfect people with power.

I don't understand what you are trying to convey here. When I purchase milk at the store, I am receiving productivity because I am paying with money. But if someone gives me the same milk, I am not receiving productivity because no money is involved? In the case of 2LT copypaster the increase in productivity doesn't do anything to the price for his labour. His wages don't go down as a result of his productivity increase.

Regardless, we don't need a theory of prices or inflation in order to trace a unit of currency through the financial system. We only need to agree on the origin and substance of money in the real world, which today comes from a bank and resides on bank ledgers digitally.

Well, the Fed is not authorized politically to disburse deposits to households. They are fully aware of the impact of QE on asset prices, that was Bernanke's stated intention ('wealth effects'). But at the very least your statement here is agreement that bank money creation is not always inflationary--in the case of QE an equal amount of reserves was not destroyed, the Fed added reserves and has not taken them out yet. I think you must concede this point, and I will re-reference this chart, which shows Fed QE yoy change correlation with CPI change (no correlation of Fed printing to CPI):

COVID reduced productivity, and reduced (constrained) supply through unforeseen bottlenecks, which has contributed to inflation in goods and services. The impact on globalization is unclear, but your speculation may be correct. But the 'irresponsible money printing' here is unclear--all money is printed, what makes some money responsible and some irresponsible? Again, genuine question, and keep in mind that banks regularly create money for increasing future output, in other words, that output doesn't exist today for purchase.

And this is where I want to get to. Neoclassical economists do not have an empirically valid theory of inflation. Post-Keynesians do. And I posted about this earlier in the thread--the Fed paper which acknowledged Post-Keynesian theories of inflation and money. When we say that the central authority doesn't understand--THEY DO UNDERSTAND. They just want something very different from you, and they are getting what they want.

Not just too much debt, too much debt which won't be repaid--unproductive debt. And, a big part of that is housing debt. Any debt which does not increase income is technically considered unproductive. All mortgage debt, consumer debt, is by that definition unproductive.

Remember, when you say 'Keynesian' you are specifically referring to the school known as 'New Keynesianism', which isn't based on the works of Keynes! It's based largely on the work of Hick's and Solow, and known as Neoliberalism, a resurgence of classical economic ideas from the 18th century. The idea that money is an exogenous commodity.

F--- the academics mate. Private debt levels and repayment capacity of constrained balance sheets matters. That's the point of all this. Everyone here needs to know how the system actually works. Trace the drop of fuel through the machine, trace the unit of bank money from creation to destruction--that way people can decide for themselves what policy is the best way forward.